Four Questions

New territory for the website! I’ll start by listing some questions I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about over the last few years.

1. How can children’s books more actively and creatively support kids learning to read?

2. How can spelling patterns be presented in ways that make learning easier and more intuitive for beginning readers?

3. Is it helpful, either for children or those who teach them, to have some sense of how our writing system has evolved over time?

4. How do we make sure the essential tools of reading and writing are fully available to everyone?

Those are all rather bottomless and enticing questions (assuming you think, as I do, that #3 demands more than a yes/no answer). I’m planning to write about each question in more depth, but for now at least I’ve written them down and posted them in public.

If you’d like to skip ahead to find out why I’m asking them (“We just want to remodel our kitchen!” “Are you still making books?”) there’s some personal explanation...well, coming soon. If you have a remodeling project, call me!

Otherwise, yes, much of my time of late has gone into reading and writing. I’ll post images of related projects in the next few sections.

The WORD GARDEN--First Prototype Now Complete!

Here's the first half of a project mapping English words in a matrix of rimes. You can read about its antecedents in the posts below. But I’ve also started a Word Garden gallery in the portfolio section of the website, where the larger image size lets me give a proper tour. See you there?

A Group Portrait

As an architect, I’m used to designing things I don’t have the skills to build. It’s strange and tantalizing in a very different way, writing a children's book for an illustrator to complete. So far it’s a bit like writing a play, and a bit like leaving an engine on the sidewalk hoping someone will build a car around it.

Anyway, I wrote a children’s book called Alphabet Potluck, in which the letters assemble an extravagant feast for all the townspeople. In doing so, I knew I was creating a host of design problems beyond my ability to conjure up answers. (If these are letters that can talk and cook and taste food, then they must have faces? Do they have arms and hands? Do you ever see them from the back, or from the sides? How do they move? Or is it more abstract than that, so that these are entirely the wrong questions? Maybe the alphabet is people wearing T-shirts? How do you emphasize character within such a large ensemble? Is there a subplot not yet invented? Or do you just focus on the food?)

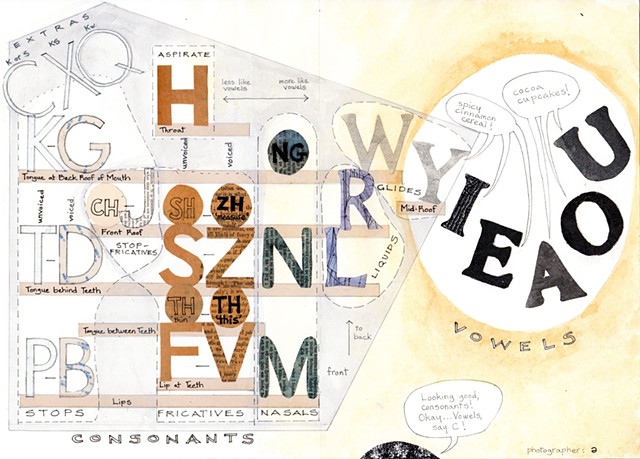

Having written the book, and feeling a delicious, humbling ignorance of what it might turn into, I started thinking about some of the casual asides and rivalries I’d included in the text. They add a layer of comedy and explication to the goings-on, but it takes a conscious mental map of English phonemes to be fully in on the joke. It’s unreasonable to expect an illustrator would happen to have that in their skill set: you can’t make a college linguistics class a prerequisite for taking on the job. In lieu of that, or at least as a starting place, I made this collage. It turns the consonant table into a photo shoot, with letters arranged by families of sounds. Consonants are standing on risers from front to back, while the vowels mill about. The goal is to translate the arcane order and jargon of linguistics into a group portrait of familial relationships. Visual elements help suggest qualities and connections embedded in the phonemes, in a way that’s hopefully legible to someone who is not a specialist.

A View of Prairie Hill

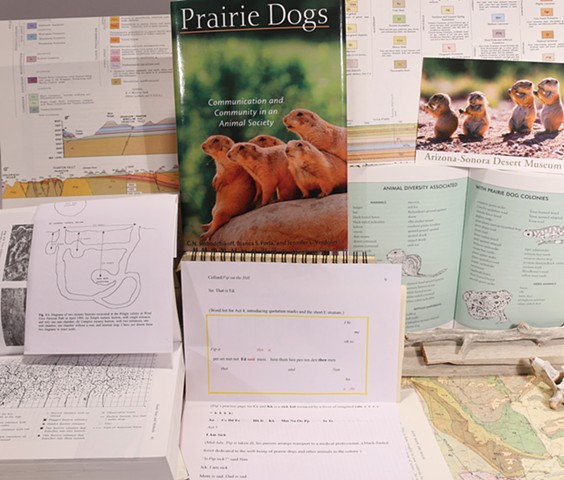

Spending time in children’s sections of libraries and bookstores, I'd been struck by the dearth of books for true beginners—for kids who are still working to master basic sound-letter correspondences, and need systematic practice decoding simple words. Why shouldn’t they have real books?

For answers I turned, as one does, to talking animals. At this point, I’ve written the first three books in a series with gradually expanding text. It seems to be working. I would really, really love pedagogical input at this point.

The Prairie Hill books are narrated by Pip, a young prairie dog who is learning to read. When I started writing in his voice, I realized the restricted text was well-suited to a coming-of-age story: that we were all learning together, and the peril and frustration of that adventure could drive some of the books’ humor.

This project is ambitious, and working on its scaffolding has led to the explorations in the following posts.

What Is a Book Made of?

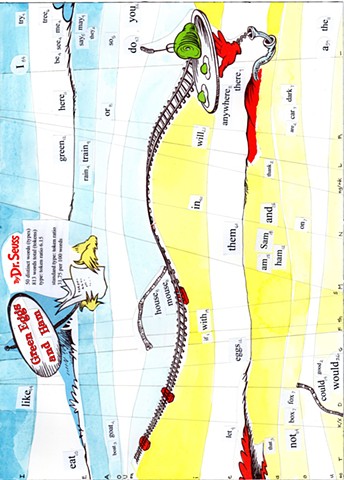

Theodor Geisel famously wrote Green Eggs and Ham using only 50 words. I was curious to look at them. Here they are.

I used WordSmith Tools to count how many times each word was used, and sized them accordingly. (“Not” and “I” both occur 84 times. “If” is only used once.) I then arranged the words on the page, based on vowel sounds and closing consonants. This being Dr. Seuss, the matrix is capriciously constructed, with not a right angle in sight. But there is an order. You can find it reading vowel sounds across, or closing consonants in columns. A railroad-track horizon divides 23 long-vowel words from the 27 with short vowels.

By giving words a location based on sound, the matrix format is a way to think about what a beginning reader needs to know, as if it were a kind of territory. We can see, for instance, that the OU of “could” and “would” shares space with “good.” But the OU of “house” and “mouse” resides in a different sector altogether. These words are simple, but also far-flung.

What the diagram leaves out, of course, is just how much Green Eggs and Ham does with its 50 words. I think we tend to remember the book’s relentless engine of escalation, but forget its finely tuned variants and pauses. The facial expressions, as characters react or fail to react to food preferences and train wrecks, are my favorite part.

What Might Another Book Be Made of?

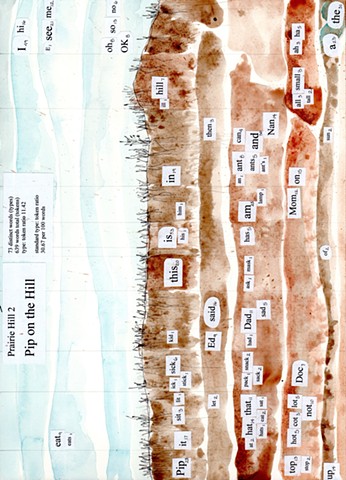

This diagram analyzes Pip on the Hill, the second book I wrote in the Prairie Hill series, using the same basic tools I used to look at Green Eggs and Ham. You can tell right away it’s a quieter book, without so much careening.

You can also see the text is mostly simple words with short vowels. This is the territory beginning readers first explore. In those critical first months, children are still learning the basics, and need systematic practice sounding out simple words. They benefit immensely from texts that allow them to use what they’ve just been taught.

The question I’ve been working on is, how do you make rich and meaningful books out of such restricted text? In a way, this diagram leaves out every answer that’s most essential. But it’s a tool to sort through some of a book’s component parts, both the nature of the words used and their degree of repetition.

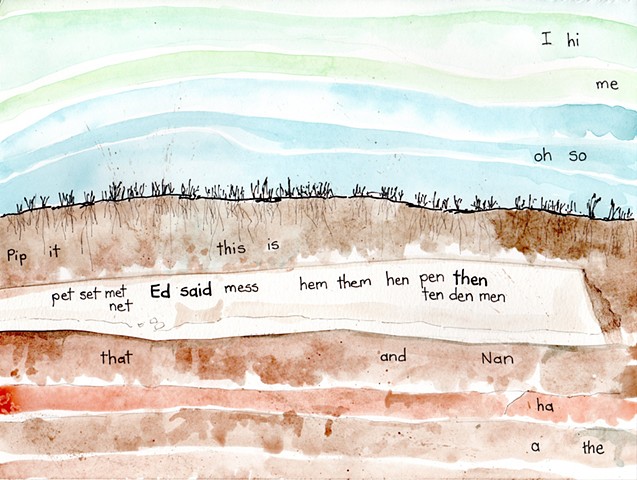

A Geology of Vowels

Here’s a word list for Act 4 of Pip on the Hill. These books are episodic, and they build systematically towards more complex text. This act introduces the short E sound, including the word “said.” It’s a very simple episode in which we meet Pip’s neighbor, a burrowing owl named Ed, and Pip uses attributed dialogue for the first time. Our view of a prairie dog’s world is expanding, and so is our guide’s ability to describe it.

There’s a tension, writing decodable text, between providing a range of examples to reinforce new material (the “frog on a log in a bog” pattern) and creating more natural sentences with fewer target words. I decided to address that tension, in part, by providing word lists at the end of each act, to show how the territory of words is expanding beyond those used in the story itself.

But how to present those word lists, so they convey patterns in an enticing fashion? Prairie dogs spend about half their lives underground, so the idea that vowels would form geological strata came pretty naturally.

I’m not at all the person to illustrate these books, but taking a first pass at mocking up some word lists helped me resolve some formatting questions I’d been stumbling over. Here you have a whole new stratum of short E words. Only three of them have been used in the main text. And what is “said” doing there, among all those Es?

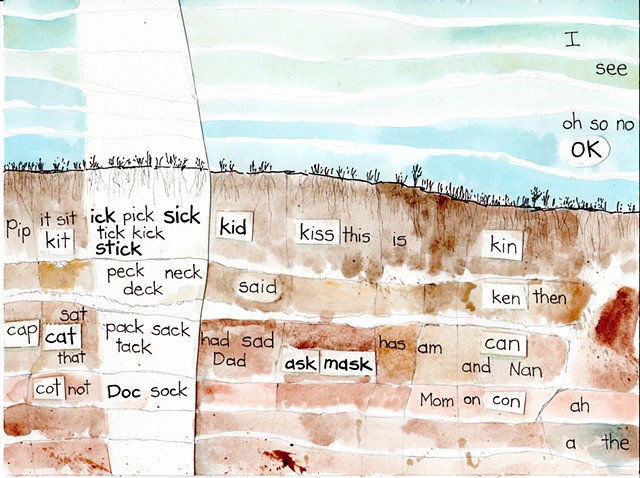

A Geology of Consonants

This is the next word list, from Act 5 of Pip on the Hill, in which Pip gets sick and is taken to the doctor, a black-footed ferret. The act also introduces C and K. The pattern of adding a consonant is more complex than introducing a new vowel layer—and even more so, when two letters are vying for the same role. Here we see a new column of words with rimes ending in the /k/ sound. There’s also a scattering of words that begin with /k/, and a couple ending in an SK blend. “OK” has joined the airy long-vowel words.

The beauty of the matrix, I think, is that it establishes a visual order based on sounds in the language. That can make spelling patterns more obvious, by giving them an aural framework in which to happen. Visual cues like alignment and proximity can play a role to help us notice what is going on. Here, the column of rimes ending in /k/ slides in next to those of other stop sounds, such as /p/ and /t/. It’s an order borrowed from linguistics, and closely tied to the alphabet’s group portrait at the beginning of this section.

Ideally, the matrix format could be a way to convey relationships without having to memorize rules or categories, putting readers in closer touch with what they intuitively know. Is that realistic? It’s a simple idea, but I don’t think I’ve seen it used for sorting words or syllables in English. I would love to get feedback on it.

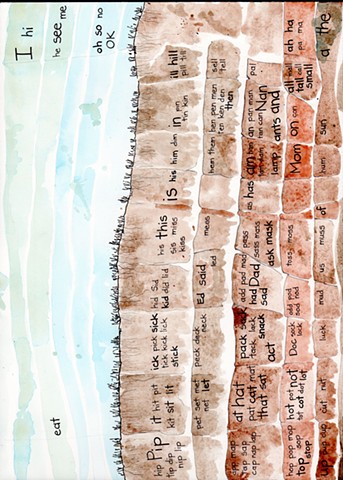

Taking Stock

One last view before we leave Prairie Hill. This one roughs out a closing spread for Pip on the Hill, one that tallies the book’s accumulations in one place. It’s closely tied to the diagram from three posts back (“What Might Another Book Be Made of?”), but includes decodable words not used in the text, as well as the words that are. The idea is to show the world of words opening up. The first book uses ten letters, and closes with a page spread of 79 root words. This one has 179 words, and the third book has 340.

It's a fairly extravagant way of taking stock, but one that conveys dramatically how far the reader has come.

Originally, I imagined these closing lists wouldn’t differentiate between words used or not used in the main text. But I’ve found I like highlighting the words we’ve been seeing.

Arranging words by sounds may also help us see patterns in our language and how we write it. I’ve arranged closing consonants by sonority (from least to most vowellike), and, within each family, by place of articulation (from front to back of the mouth). Both those factors impact how the sounds behave: how they interact with vowels, and where they occur in consonant clusters. As we add words, patterns will become more visible. Rimes ending in open vowels will continue to waft skyward, a column of short, indispensable words.

I would love to get pedagogical feedback on what I’ve done so far, before moving ahead with these books, making revisions, or taking steps toward publication.

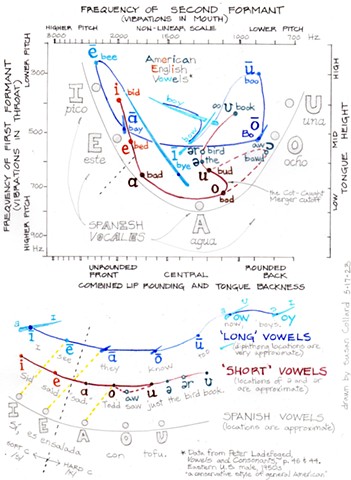

A Goblet of Vowels

This diagram is quite wonky, and basically a proof-of-concept study as I was designing the matrix format for the word lists.

The closing consonants’ format was straightforward. But what is the best order to stack layers of vowels? I drew this diagram to test my basic approach, and to find logical spots for “leftover” vowels. I wanted to:

1. preserve our conventional distinction between long and short vowels

2. keep similar sounds close to each other

3. separate vowels that take C from vowels that need K for the /k/ sound

4. keep things as simple and intuitive as possibleI drew this diagram by combining two charts from the phonetician Peter Ladefoged mapping resonances of the human vocal tract. The curve at the bottom, which reminds me of a goblet, marks the boundaries of this “vowel space.” The five Spanish vowels make a nice, tidy lineup near the edge of the vowel space. English vowel sounds are messy and volatile, but written with the same alphabet, and I like to think of them cradled by an ideal Spanish IEAOU.

I’d say the order IEAOU seems to be working, based in part on the ability to plot plausible curves through the neighborhoods of sounds. It definitely does a better job with Missions 2 and 3 than would our usual AEIOU. At this point, I feel like I’m still fine-tuning the matrix for Mission 4.

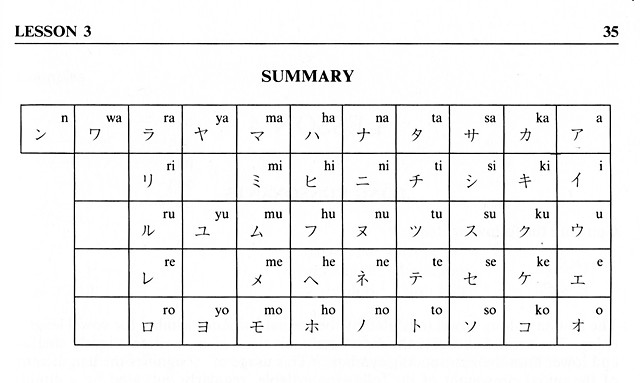

Mapping a Language: Japanese

Where did the matrix idea come from? I took Japanese as an undergraduate, and that might have something to do with it.

You can’t do anything like this with English—the syllables are way too messy. But, oh, it was beautiful, after months practicing basic conversation, to see the units of the language stacked in a neat array.

(Katakana table from Reading Japanese, by Eleanor Harz-Jorden and Hamako Ito Chaplin.)

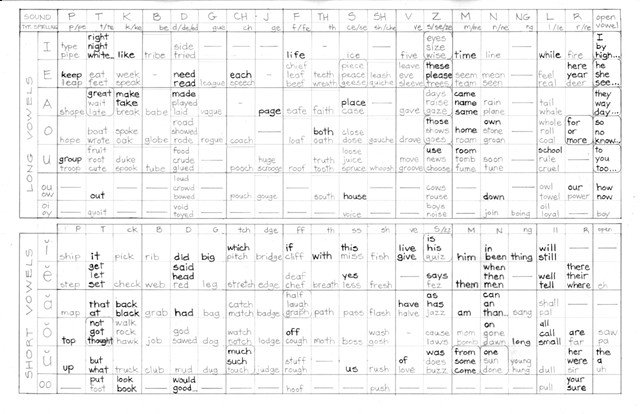

Mapping a Language: English

English resists a concise overview. But what would happen if we made the attempt?

This is a chart of one-syllable words ending in a single consonant or open vowel. I used the Phinder tool from Devin Kearns’ website to select the most common word for each spelling pattern. Words shown in bold are in the top 200 of Devin’s list of high-frequency words.

I've been doing further work on this idea, so if you'd like to see more developed versions please let me know. I'm especially interested in ways to expand each cell to host a full range of words--not just "am," for example, but also "camp" and "camera"--without losing the clarity of the basic matrix. I'm currently working on a prototype which might be used in the classroom. Each active plot of the Word Garden would have a little unfolding booklet, curated to move from one-syllable words to increasingly complex morphologies. Yes, that's a lot of curating, but it's also a revealing way to explore the territory of written English. The general effect is something between a periodic table of the elements and an advent calendar.

Several months later, there are photos of the prototype in the Word Garden gallery.

There's also a list of one-syllable words utilizing the matrix format posted on Google Drive.

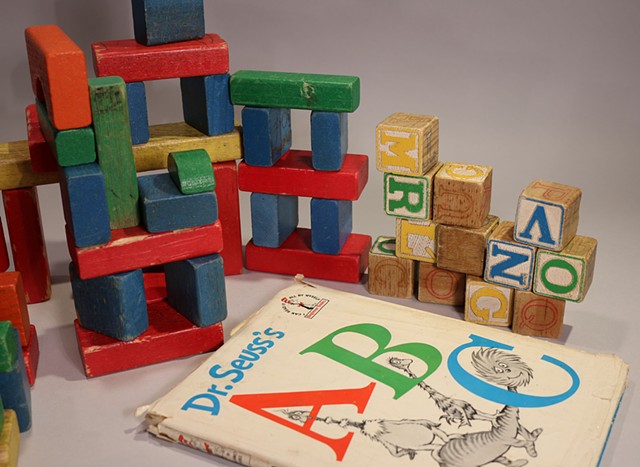

A Childhood Design Problem

As a kid, I was very fond of the alphabet, and of building blocks as well. Alphabet blocks? Not so much. If you think about it, they’re not really well-suited for either building or spelling. They don’t have the dreamy proportions and hierarchies of our old red and blue set. In fact, they eschew the neolithic innovation of post-and-lintel structure altogether! And they revel in randomness. Whatever letters you’re looking for never seem at hand.

The Alphabet as Kit of Parts

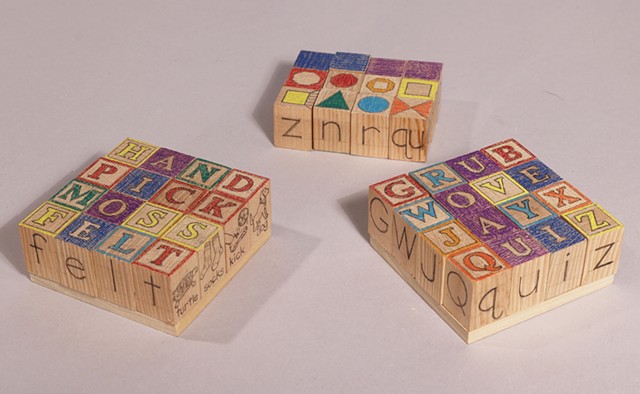

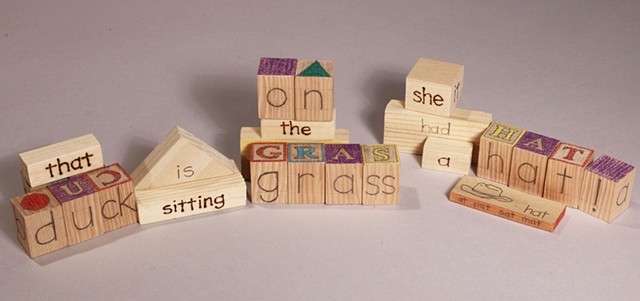

This is a side project I started in 2022, when I was fussing with word lists for the Prairie Hill books and struggling to explain what I was trying to do. In the two starter sets in the foreground, every block is just one letter. Family blocks in the back gather lowercase letters with related phonemes.

Kit of Parts 2

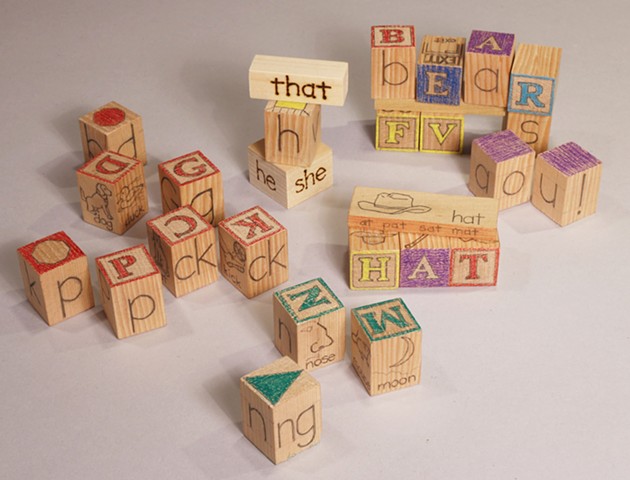

The blocks are designed to invite sorting. Their sides have 4:3 proportions, so they’re taller than a cube, and a bit more dynamic. A kid could place them all right side up, even before recognizing letters. (Or upside down, if they wanted to look at the shapes on the bottom.)

Colorful shapes at the bottom of each letter block match the top face of a family block. Stop sounds are red, naturally enough. Sounds on the left in the photo are unvoiced, and those on the right are voiced. But no one needs to fuss over that, right? They're just blocks that go together, if you happen to have noticed that. The ones with the sign on top have extra letters you might want to use sometimes.

Kit of Parts 3

There is something about being able to pick a thing up and inspect it. Or taking a set apart and deploying it. Noticing its fiddly bits. Building things, and knocking them down again. Fitting the set back together. Or turning the pages of a lovely and surprising book. These are fundamental aesthetic pleasures, of a kind that those of us who make artists' books more or less live for.

“I would argue that any theory of human intelligence which ignores the interdependence of hand and brain function, the historic origins of that relationship, or the impact of that history on developmental dynamics in modern humans, is grossly misleading and sterile.”

--Frank R. Wilson, The HandKit of Parts 4

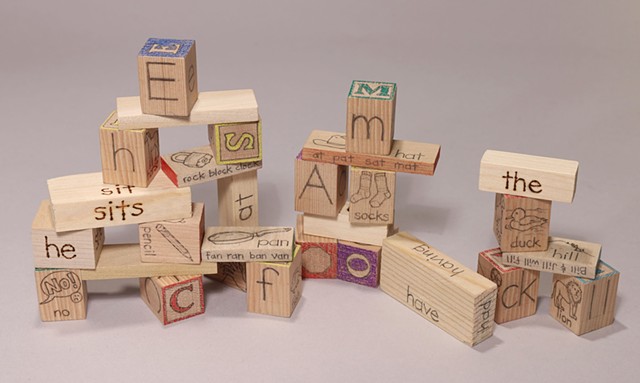

The prototypes are rather time-consuming, so I put this project aside to focus on the writing. If developed, I think there are possibilities for bringing in syntax and morphology in ways that celebrate a complex, lively, integrated system. Not an ideal one, but one that struts its quirks.

Kit of Parts 5

And possibilities for post-and-lintel!